Luxury brands thrive on their exclusive products. The most prestigious of brands, like Hermès and Rolex, are infamous for their long wait times to buy new products, either because the stock is sold out or because the sales teams are picky about who they sell to. Instead, interested buyers are often advised to build relationships with these brands’ sales associates for a better chance of being moved up the waiting list.

This business model has long gone unexamined, from a legal perspective, but a new class action lawsuit filed this week by two California law firms, Haffner Law PC and Satareh Law Group, seeks to change that. The suit, filed in California against Hermès, alleges that the brand’s sales practices unfairly require customers to make multiple ancillary purchases to get to the product they actually want: a Birkin bag. In doing so, the plaintiffs allege that Hermès has violated the Sherman Act, an antitrust law that forbids “unilateral conduct that monopolizes or attempts to monopolize the relevant market.”

In the court filing, attorneys Joshua Haffner, Alfredo Torrijos, Vahan Mikayelyan, Shaun Setareh and Thomas Segal argue that Hermès has “illegally tied” the purchase of a Birkin bag to a customer’s prior purchase history with the brand. It’s also “willfully and intentionally engaged in predatory, exclusionary and anticompetitive conduct” to “[maintain] its market and/or monopoly power,” according to the filing.

“The unique desirability, incredible demand and low supply of Birkin handbags gives Defendants incredible market power,” the complaint alleges. “Defendants implemented a scheme to exploit this market power by requiring consumers to purchase other, ancillary products from Defendants before they will be given an opportunity to purchase a Birkin handbag. With this scheme Defendants were able to effectively increase the price of Birkin handbags and, thus, the profits that Defendants earn from Birkin handbags.”

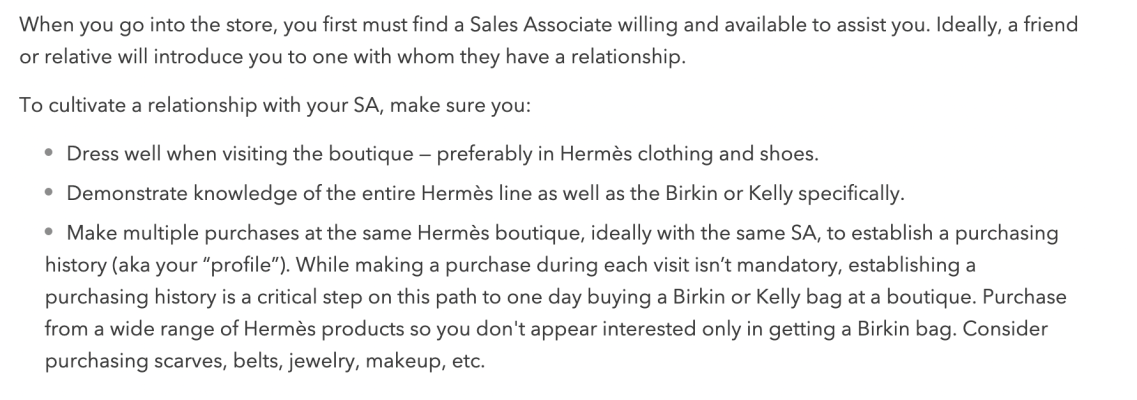

Hermès’s policy on who can to buy a Birkin bag in its stores is famously opaque. There are numerous guides about how to make a good impression when shopping for a Birkin in the hopes of getting moved up the list, including making multiple purchases and dressing well on each visit to the store.

The filing cites the experience of one of the two plaintiffs, Tina Cavalleri, who was told by an Hermès sales associate that she could not buy a Birkin because they were being saved for “clients who have been consistent in supporting our business.”

Whether this constitutes a violation of the Sherman Act will be decided by the courts, but some legal experts think the plaintiffs’ arguments will face a tough challenge in court.

“I don’t think the theory of the case is frivolous, but I do think the plaintiffs will face significant challenges establishing that Hermes’s practices hurt competition to an extent that constitutes an antitrust violation,” said Rob Freund, a lawyer who has represented apparel companies in California.

Freund said Hermès’s likely defense in court will be that it does not control the entire luxury handbag market and, therefore, cannot be called a monopoly. After all, there’s nothing stopping customers from going and buying a luxury handbag from another brand. There’s also resale through platforms like Fashionphile or Rebag, which requires no complicated relationship-building before purchase. Therefore, the potential argument would go: “There are many ways to get a Birkin bag.” Hermès did not respond to request for comment on this story.

“While the plaintiffs may feel wronged, establishing antitrust violations could pose a formidable challenge,” said Elise Whang, former attorney in the Division of Advertising Practice with the Federal Trade Commission and current co-founder and CEO of luxury resale wholesaler LePrix. “Last I checked,you cannot have a monopoly on your own product. They could always look into buying a beautiful pre-owned Birkin as an option. As a private business, Hermès can design its customer experience and brand strategy as they wish as long as they do not discriminate against a class of people.”

But a win is not guaranteed for Hermès, particularly in California where the courts tend to be more aggressive about cracking down on anticompetitive practices. If the plaintiffs were to win, other brands in the luxury industry with a similar model — Rolex being the most obvious offender — will likely take notice.

“[The plaintiffs winning] would not impose any kind of direct obligation on any other business,” Freund said. “I would expect other luxury brands will pay attention to this case, and even if Hermès doesn’t win, they will closely evaluate whether they need to make changes.”