Dove has been known for championing self-esteem for almost as long as it’s been known for its iconic bar soap. The brand first debuted its Self-Esteem Project in 2004 and has since been investing in championing self-esteem for women. That includes extensively advocating for The Crown Act, which it has done since 2018.

On Tuesday, it debuted on its website a 161-page report that it commissioned, titled “The Real Cost of Beauty Ideals.” The culmination of its partnership with STRIPED (Strategic Training Initiative for the Prevention of Eating Disorders) at Harvard’s Chan School of Public Health and economists at Deloitte Access Economics, it examines the cost of beauty standards on the U.S. economy and society.

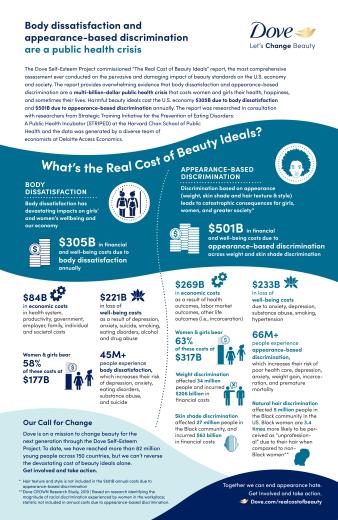

The report examined two main “pathways” through which these costs accumulate. The first is body dissatisfaction, which the study defined as “having a severe negative attitude towards one’s own physical appearance,” which “originates from a perceived discrepancy between an individual’s ideal state of appearance (i.e. the beauty ideal) and their actual physical appearance.” The study found that body dissatisfaction results in $305 billion of financial and well-being costs annually in the U.S.

The second “pathway” is that of appearance-based discrimination, which the study examined with regard to weight, skin shade, and hair texture and style. This amounts to $501 billion in annual financial and well-being costs in the U.S., according to the report.

“We hope this report will help support systemic change against racist and gendered beauty ideals, it is the most comprehensive assessment ever conducted on the pervasive and damaging impact of beauty standards on the U.S. economy and society,” said Ale Manfredi, Global Chief Marketing Officer at Dove. “The report proves that beauty standards are not superficial. They have a human and financial cost that we must all address and work together to campaign for change, so that a positive relationship with beauty can be accessible to all and everyone can reach their full potential.”

These costs manifest in a number of ways, said Simone Cheung, partner at Deloitte Access Economics. “The first type of cost is a cost to the system. It’s the cost of people accessing services in the system, because they are dissatisfied with their body or they are being discriminated against.”

For example, body dissatisfaction means an increased likelihood of having mental health conditions. “Having an eating disorder or another type of mental health condition means you have to access mental health services — and that’s a cost to the system. We looked at the financial cost of you accessing government services or the private services,” Cheung said.

“The second type of cost is a non-financial cost. That includes [a person] not being able to go to work because of [their] mental health condition, binge drinking — whatever it might be. There is a cost associated with that; you have a loss of productivity.” Finally, the biggest cost is the cost of the “loss of well-being,” she said. These are costs to the individual, resulting from body dissatisfaction or appearance-based discrimination. Examples include depression, suicide, smoking, eating disorders, alcohol and drug abuse.

Cheung added, “We often think about [these issues as impacting] girls and women, and it’s true that [the majority of impacts are on women]. But men are also impacted by body dissatisfaction, especially young men.” Men often experience appearance-based discrimination around height, in particular, Cheung said.

Though plenty of research exists on the damaging impacts of body dissatisfaction and appearance-based discrimination, Dove’s study marks the first time researchers have quantified the costs of these issues.

The findings of the research can feel a bit doom and gloom, but Dr. Bryn Austin, founding director of STRIPED, said she’s hopeful about the future. “There are advocates and policymakers who are working hard to address these issues,” she said.

“Right now, weight-based discrimination is legal almost everywhere in the country. One state has prohibited weight-based discrimination — that’s Michigan. And six cities in the U.S. in the last decade or so have passed protection, prohibiting unfair weight-based discrimination,” she said. By early 2023, she predicted, “We’re going to see more states pick this up, because people don’t want to see this kind of unfair treatment.”

Of course, on the flip side, this means that 96% of people in the U.S. currently live in an area where they have “absolutely no protection” from being docked pay or fired from their job because of their weight.

There is also momentum when it comes to legislation around the “insidious effects of diet culture.” For example, “downright dangerous” diet pills are completely unregulated, Dr. Austin noted. But in New York and California, “state legislatures have passed bills to ban the sale of over-the-counter diet pills to children younger than 18. And in both states right now, those bills are sitting on the desks of the governors in both states.”

In terms of what’s next, Manfredi said, “Legal protections against discrimination based on narrow beauty standards and racist and gendered systemic biases need to be in place, and Dove is committed to progressing these efforts as we work to change beauty.”